Editor's note: This article was produced by a student participating in the course J473/573: Strategic Science Communication, a collaboration between the School of Journalism and Communication’s Science Communication Minor program and the Research Communications unit in the Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation.

Imagine a world in which biomedical engineers are able to produce functional human organs with the help of 3D printers. Though it might sound like science fiction, futuristic goals like this are exactly what researchers like Patrick Hall, a bioengineering and biomedical engineering PhD candidate, are working toward. Since starting his studies at the University of Oregon back in 2021, Hall has spearheaded research on manufacturing efforts with volumetric additive manufacturing (VAM), an unconventional form of 3D printing. Hall uses VAM to continue to build the scaffolding on which other bioengineers will hopefully be able to one day fully recreate human organs, tissues, bone marrow, and other naturally occurring components in the body. Hall’s efforts have allowed him to reduce the cost of VAM from $25 per print down to only 2 cents, an extremely economical price for printing with medical-grade materials.

“VAM excites me because I am able to use this new 3D-printing technique to print things with better physical properties and better resolution, compared to others in the field while also reducing the cost a ton,” Hall said. “It is also just a lot of fun to collaborate with other labs in the building… it was really like a big kind of steppingstone for me.”

Building bonds between polymers and projects

When compared to other forms of 3D printing, VAM has a much faster turnaround time; it takes less than a minute for a prototype to print from start to finish. Now that Hall has found a way to reduce the price to only a couple of cents per print, the possibilities of utilizing VAM techniques in biomanufacturing are endless. VAM’s reduced price per print in addition to its rapid turnaround time helps Hall’s research move at a quicker pace. Therefore, he is able to share his findings with other scientists faster than ever before.

VAM is one of the primary printing techniques used in the Dalton Lab, a multifaceted, advanced bioengineering research group located in the Phil and Penny Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact. The Dalton Lab is led by Paul Dalton, the Bradshaw and Holzapfel Research Professor in Transformational Science and Mathematics at the Knight Campus. In the lab, Dalton and his team focus on trying to improve and push the boundaries of both pre-existing and newly invented 3D printing manufacturing techniques. Dalton’s many years of experience with advanced biomanufacturing have made him the ideal mentor for Hall to collaborate with while working on manufacturing new printing techniques and biomaterials to be used in VAM. Although Dalton has helped oversee Hall throughout the process of customizing 3D printer software and creating new biomaterials to be used in the printing process, Hall has taken the reins of making VAM more accessible to both the researchers in the Dalton Lab and beyond.

“This is really where Patrick stepped up to the challenge of trying to make low-cost prints, and now it's only two cents per print,” said Dalton. “Improving accessibility of VAM through the drop in price is one of the outcomes that I'm really happy with, and again, Patrick led a lot of the work on the volumetric printing.”

Turning photopolymers into 3D prints

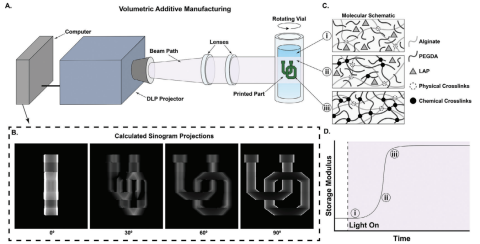

VAM is one of many forms of bioprinting, a type of 3D printing used to create a variety of functional structures and scaffoldings. After being printed, these structures can be used in the process of medical engineering, for example, tissue or organ manufacturing. Unlike other forms of 3D bioprinting, VAM prints into a small vial of photopolymerizable resin, which is a specific type of resin composed of large molecules called photopolymers that can change properties when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light. It is similar to the process of getting a manicure with gel nail polish. When the manicurist puts a person’s nails under a UV light, the polish hardens, just as the photopolymers do when they are exposed to UV light which are projected as specific shapes.

The process of photopolymerization allows scientists like Hall to use materials called hydrogels to design complex structures with intricate details that the normal, bottom-up process of 3D printing cannot create. Hydrogels are water-based polymer networks, similar to Jello, that have properties very similar to living tissues in the body.

VAM uses UV lights that flash sequentially at different angles into a rotating vial of resin. The printer goes through several rotations and eventually the shape adds up until it passes the threshold of enough light to harden. “It’s a process that takes less than a minute,” Hall said.

VAM is used to instantaneously create structures that are only 4 to 12 millimeters wide but can hold their shape in water. For example, Hall has used the VAM printing technique to manufacture double helix structures, expandable and collapsible interlocked chains, and even a miniature hot air balloon.

Printing our way forward

When looking to the future, Hall would like to continue working in the printing space, using his skills to develop techniques for companies to help improve how consumers in the scientific community utilize 3D printing. Luckily for Hall, he is surrounded by a team of scientists who are also eager to make an impact.

“I just refuse to accept that we live with diseases and injuries and there's nothing you can do about it. Absolutely not,” said Dalton. “The more focus we put on treating diseases, the more diseases we will be able to treat and then also the material can be translated to the clinic. I think that's kind of the that economic angle is really where I see there's a lot of equity that can be achieved.”